Windows Phone: Background Agents Pitfalls (1 of n)

Published on Sunday, February 19, 2012 7:24:00 PM UTC in

Programming

There's a ton of resources available on the web that talks about the new features of Windows Phone 7.5 "Mango" for developers, and about background agents in particular. Unfortunately, a lot of these resources use over-simplified samples that have little in common with complex real-world setups, and often the articles you can find don't even mention the several restrictions in place for background agents at all. In this open-ended mini series I am going to talk about the various problems you will potentially run into with anything but the most trivial applications, what effects and consequences this has for your application development, and how you can avoid pitfalls and plan ahead for background agents. This is not a general introduction on the topic; I assume that you are familiar with the concept and have a basic understanding on how agents work.

Part 1: API restrictions

When you work with background agents, a lot of restrictions on the APIs you are allowed to use are in place. Most of these restrictions are understandable and either simply a logical consequence of the fact that agents do not have any sort of UI or other forms of user interaction, that agents do not run in the same full runtime environment that is spun up for normal applications, or they are in effect to prevent malicious behavior. You can find a list of these unsupported APIs in the MSDN documentation here.

One of the pain points with this however is that your agent runs through a static code analysis during submission (or when you use the Marketplace Test Kit) that is not intelligent enough to determine whether you're actually using those APIs from within your agent, or not. This means that any of your code or referenced assemblies or projects in your solution make use of unsupported APIs, you'll receive errors during the capabilities validation, and as a consequence your application will fail the test cases. Let me discuss these problems using a few real-world examples.

Setup

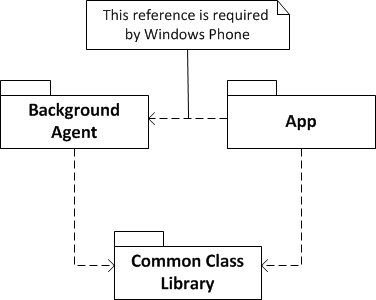

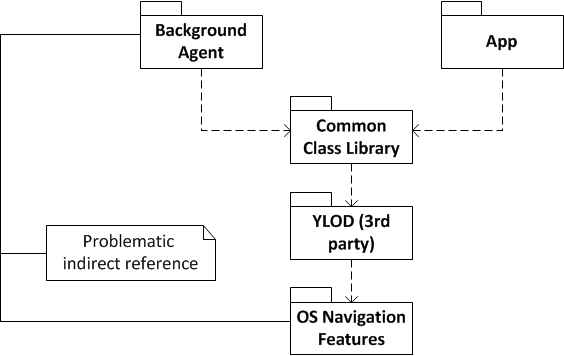

The usual setup when you want to integrate background agents in your application is to refactor your existing code base so both the agent assembly and your main application share a common set of components or libraries. This enables your agent to e.g. use the same code for configuration, loading data etc. as your application:

This simply is following the principles of modular programming (DRY) and should be common sense among developers. As soon as you start working with such a setup, I recommend to make use of the Marketplace Test Kit often, starting early on in your development process, to identify any of the discussed points below as soon as possible. This allows you to apply needed refactoring or change your software design when it's still cheap to do.

Example 1: Smelly Code

Problems often arise when you don't closely follow best practices like the principle of single responsibility. In many of these situations it's not developers being lazy or inexperienced, but the fact that the limited resources on the phone sometimes seem to require to let go of decoupling and isolation down to the very last detail. Additionally, most of the available online samples in the MSDN docs are not helping with these issues either, as they often simplify and don't put emphasize on the value of these patterns or best practices (which is, given their purpose, understandable).

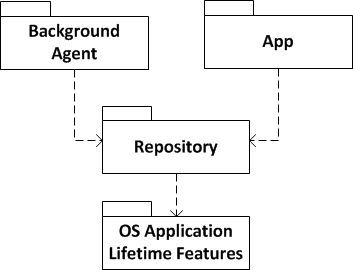

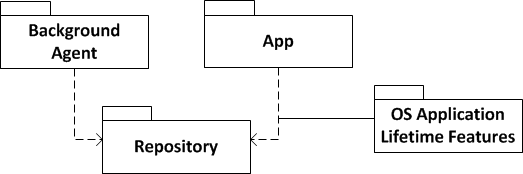

Let's say you want to create a central repository in your application that handles data persistence in a nice way. What you probably need to do is add some initialization and tear down logic that is executed at certain points of the application lifetime (launching/activation vs. deactivation/closing). What I often see when I review apps is that people create that persistence layer in a way that it is able to handle the phone's lifetime events internally. Since we have convenient access to a global PhoneApplicationService instance everywhere, this is pretty easy to do, and the result is that you have a completely encapsulated package of a repository, that has a very limited public surface for initialization and shutdown.

The problem is that when you now try to use your persistence implementation in your background agent (which is a perfectly legitimate thing to do), you will receive validation errors, because it's not allowed to hook into the lifetime events of the phone's application service from a background agent. Even if you implement your code so that you can turn off this behavior when it is running in the context of the agent, validation will still fail. The fact that you're referencing the APIs in question, even if they're not actually invoked at runtime, is sufficient to break the tests.

In these simple cases it's easy to resolve the problem; in our example, you would simply follow the principle of single responsibility, and handle the phone's lifetime events from outside the repository and call its respective methods for initialization and shutdown, so you don't need to reference them from within your code.

Example 2: Excessive Granularity

There are some cases where the granularity of the list of supported APIs is so detailed that the restrictions themselves make it impossible for you to satisfy the requirements in a clean way, even when you follow every best coding practice. Let me give you an example for that. In the list of unsupported APIs I've linked to above, you can find the following entry:

| Namespace | Unsupported API |

|---|---|

| Microsoft.Phone.Shell | All APIs are unsupported except the following: |

| ShellToast class | |

| Update(ShellTileData) method of the ShellTile class | |

| Delete() method of the ShellTile class | |

| ActiveTiles property of the ShellTile class. |

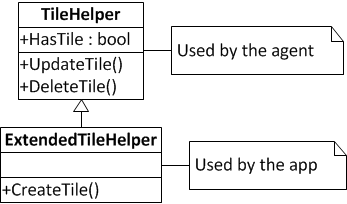

As you can see, the differentiation here goes all the way down to individual methods and properties of certain classes. The motivation of course is perfectly clear and understandable: for obvious reasons an agent should not be allowed to create new tiles, for example. For you as developer this however creates a whole new set of problems. If you want to work with a combination of agents and secondary tiles, you are obviously going to use all parts of the available API: you will create new secondary tiles from within your application, and you also want to update the tile's content from within your background agent when new data is available for display. That fancy class you created for this, which nicely does all the tile creation and updating for you cannot be used from within your agent, because referencing the Create(ShellTileData) method of the ShellTile class is not allowed. This is the point where re-using existing code and modularizing your components breaks. How do you solve that?

In our sample, the public interface of our class (without the implementation details) would probably look something like:

public class TileHelper

{

public bool HasTile { get; }

public void CreateTile(int itemCount, string message);

public void UpdateTile(int itemCount, string message);

public void DeleteTile();

}

Conditional Compilation/Partial Classes

One way of solving this is to use linked code files and conditional compilation. Basically, the idea is to add a conditional compilation symbol to your agent project settings (for example "BACKGROUNDAGENT"). Then you can update the code to:

public class TileHelper

{

public bool HasTile { get; }

#if !BACKGROUNDAGENT

public void CreateTile(int itemCount, string message);

#endif

public void UpdateTile(int itemCount, string message);

public void DeleteTile();

}

Using Visual Studio's linked file feature, you can then include the file in multiple places (the background agent and your main application), and depending on the context the critical APIs will be included in the compiled result, or not. Similar approaches use linked files in combination with partial classes, to physically structure and separate the individual parts a bit nicer.

I dislike this version a lot; usually it leads to follow-up problems because due to the required assembly references for background agents the file effectively is included multiple times and produces naming conflicts and potentially confusing errors ("ambiguous reference"). This forces you to for example also change the namespace declaration based on the conditional compilation symbol, so the naming conflict is resolved properly. This leaves two versions of your components in separate namespaces, and can lead to a poorly maintainable and hard to understand code base quickly.

Inheritance

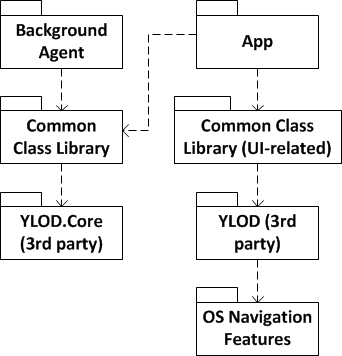

Another solution is to use inheritance (or, sometimes, aggregation). Often you can split the problematic classes into derived classes, and put those classes into the agent and app (or into separate class libraries used by the agent and app). Then the setup would look like this:

I also don't like this second version very much, but to me it seems like the lesser evil compared to the linked files workaround described above.

This is a situation where a technical restriction directly affects your software design, and even forces you into giving up some of your perfectly valid code structures. It is another reason you should make use of the Marketplace Test Kit often, so you can identify these problematic places quickly.

Example 3: External Libraries

This is the most critical aspect, because if you're running into problems with external libraries with your background agents, solutions often require the support of the original author of that library. The potential problems in detail are exactly the same as with your own code: the author of a library needs to be aware of the scenario that their component will potentially be used in a background agent, and accommodate for the multiple limitations and pitfalls in their own code.

I am guilty of not paying enough attention to this aspect myself; let me quickly explain what happened. I'm the author of a few open source libraries available on CodePlex, and one of that libraries is named "Your Last Options Dialog". The idea is to save you the time of creating an option dialog for your Windows Phone application and do that automatically for you (very similar to one of my other projects - YLAD - which does the same for about dialogs and has reached a bit of popularity). You simply use one of your already existing POCOs, pass it to the component, and it auto-magically creates the options page(s) for you, using a pre-defined set of controls to edit the POCO properties, based on their types. Now, to give you as a developer some ways to influence the appearance and structure of that dialog, I added the possibility to annotate your POCO properties with certain attributes the component understands. And here comes the problem.

Imagine that the POCO you're using for the YLOD project is a central part of your persistence logic, for example the data container you use in serialization to and from isolated storage. Then you probably want to also use this type in your background agent for one or another reason. However, to use this settings class which is now decorated with YLOD's attributes, you also need to reference the YLOD assembly - and there you go, since YLOD uses various APIs to navigate between pages and other things, your background agent fails validation.

This is another example of how validation of your own background agent (and hence application) can fail even though you're not actually doing anything forbidden. The simple fact that an external library in turn has a reference to an unsupported API is problematic. And in these cases, like I said, there's often little you can do yourself to solve the problem.

YLOD of course has since been updated, and its safe core features like the annotation attributes have been refactored into a separate assembly, which now allows you to use your settings POCO container from your background agents even when they're using the YLOD attributes (this improvement is available starting in version 1.0 of YLOD):

This pattern is also suitable to structure your own code into parts that are safe to use from background agents, and those that are only valid to use from the full app.

Conclusion

I think the examples demonstrate that the really nice new feature of having background agents comes with strings attached. You have to carefully plan ahead some of the aspects and think about what parts of your components you're going to use in your background agents code, or you will face painful and unexpected refactoring work later on in the development process. Sometimes this can be solved with a simple restructuring of your code, sometimes it requires more complex work like creating multiple satellite class libraries, or working with shared files or additional inheritance. The worst case is that you cannot resolve the situation yourself at all when you're using third party libraries that do not support background agents, and that you have to rework large parts of your application logic because of that.

I hope you enjoyed this first part of the mini series; if you have additional thoughts or want to comment, feel free to leave me a note below, or contact me directly. In the next part I'll continue to look at additional challenges you as developer have to master with background agents. Stay tuned!

Tags: Background Agents · Windows Phone 7